Szilveszter Makó Inside and Out of the Box

Feb 6, 2026

Before a shoot begins, Szilveszter Makó likes everything to be visible at once. Clothes hang in suspension. Props accumulate. Tape marks the floor with provisional intent. Nothing is yet decided, and that is precisely the point. For Makó, an image is not executed; it is negotiated—between control and chance, discipline and disruption.

Makó grew up in Miskolc, an industrial city in northeastern Hungary, and is now based in Milan. He is not signed for representation, a detail that feels less accidental than principled. His work carries the density of someone who insists on authorship at every level. These are not images that glide into existence. They feel built, textured, laboured—composed with the patience of someone who believes that meaning appears only when chaos is contained.

His path into photography was indirect, shaped by restless creative exploration. As a teenager, he photographed hairstyles he created himself, documenting them obsessively. Even then, photography was not simply a medium but a tool of control—a way of fixing a fleeting moment and deciding how it would be remembered. He resists calling himself a photographer. The image, for him, exists before the lens. Photography is merely the mechanism that allows him to impose rules.

Those rules are visible in the foundations of his work: natural light and texture. Texture, especially, operates as an emotional surface. His images seem worn by time, as if touched by hand. Though he works across analogue and digital processes, his post-production methods remain deliberately opaque. Not out of mystique, but out of preservation.

Those rules are visible in the foundations of his work: natural light and texture. Texture, especially, operates as an emotional surface. His images seem worn by time, as if touched by hand. Though he works across analogue and digital processes, his post-production methods remain deliberately opaque. Not out of mystique, but out of preservation.

He is uninterested in perfection. What he pursues instead is idealisation—an echo of classical sculpture, where reality is bent rather than reproduced. His figures are not aspirational models or instructions for how to look. They are closer to characters in a novel: encountered briefly, then left behind.

That restraint is rooted in biography. Makó was raised by grandparents shaped by the severity of Eastern Europe’s twentieth century—disciplined, conservative, resilient. Factories, coal dust, and bare brick walls formed the visual grammar of his childhood. Structure was not aesthetic; it was survival.

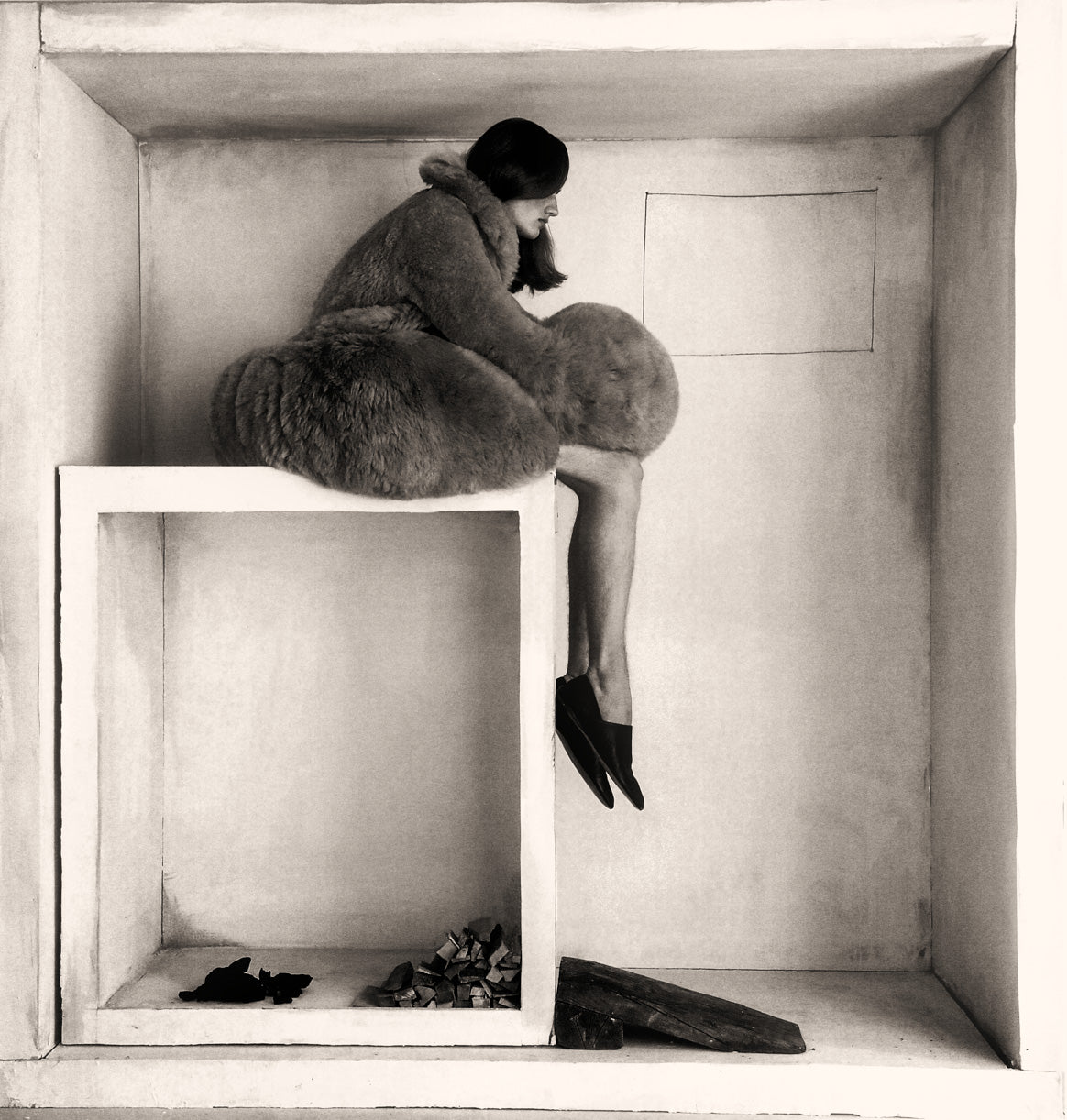

Makó has spoken openly about being on the autism spectrum, about a mind drawn to order and precision. This manifests most clearly in what has become one of his defining motifs: the box. Simple, almost banal, the box functions as both container and amplifier. By enclosing the subject, it prevents energy from scattering. Meaning gathers because the image is not allowed to sprawl.

Over time, the box has evolved. Physical constructions gave way to painted outlines on the studio floor, flattening the form into something lighter, almost spectral. Discipline remains, but its weight dissolves.

Over time, the box has evolved. Physical constructions gave way to painted outlines on the studio floor, flattening the form into something lighter, almost spectral. Discipline remains, but its weight dissolves.

On set, Makó balances discipline with openness. Certain gestures recur in his work, but he protects space for the unforeseen. He distrusts over-control. A shoot must be allowed to breathe.

One of his most personal images emerged while photographing Willem Dafoe, placing the actor’s head inside a house-shaped structure rooted in Makó’s own childhood memory. The image marked a turning point in his career.

Recently, Makó spent weeks travelling alone in Yunnan, China, immersing himself in minority cultures and traditional dress. Known for muted palettes, he found himself confronted with colour used as daily life. He is still digesting what this encounter will mean.

“What doesn’t exist, I create,” Makó has said. The line reads less like a slogan than a method. He builds worlds from fragments—memory, gesture, material, and rule.

In an industry built on clarity and repetition, Makó’s images insist on something slower and more private: spaces shaped by discipline, where imagination survives intact.